Julio Rocha do Amaral, MD e Renato M. E. Sabbatini, PhD

When a medicine is prescribed or administered to a patient, it can have several effects. Some of them depend directly on the medicine's pharmacological action. There exists, however, another effect, that is not linked to the medicine's pharmacology, and that can also appear when a pharmacologically inactive substance is administered. We call it placebo effect. It is one of the most common phenomena observed in medicine, but also a very mysterious one.

The placebo effect is powerful. In a study carried out at the University of Harvard, its effectiveness was tested in a wide range of disturbances, including pain, arterial hypertension and asthma. The result was impressive: 30 to 40% of the patients obtained relief with the use of placebo. Furthermore, the placebo effect is not limited to medicines but it can appear with any kind of medical procedure.

In a trial to test the value of a surgical

procedure (ligature of an artery in the thorax) to treat angina pectoris

(pain in the chest caused by chronic heart ischemia), the placebo procedure

consisted in anesthetizing the patient and only cutting his skin. The thus

fictiously treated patients showed an 80% improvement while those actually

operated upon only 40%. In other words: placebo acted better than surgery.

What is the placebo effect? How can it be explained?

In this paper we shall examine the neurobiological bases of the placebo effect, according to the most recent hypotheses. The study and better understanding of the placebo effect, and its place in medicine, has a great importance for the therapeutical act, besides having great ethical repercussions in medical practice and research. We shall focus our explanations upon a specific type of placebo, the pharmacological agent (medicine). But the principia we discuss in this paper can be generalized to any type of placebo.

"Placebo is any treatment devoid of specific actions on the patient's symptoms or diseases that, somehow, can cause an effect upon the patient."Pay attention to the difference:placebo is an innocuous treatment. Placebo effect is the result obtained by the use of a placebo. A placebo effect is not induced by every placebo. Nevertheless, a placebo effect can only follow the use of a placebo. Did you get it?

The knowledge about the placebo effect was very much enlarged with the medical need to perform controlled clinical trials,a scientific methodology largely used to determine the therapeutic effectiveness of new medicines.

In these trials a placebo is obligatorily administered to a control group of patients, and later the results of this group are compared with those obtained in the group that receives the active medicine, whose action one intends to demonstrate. The bigger the difference in the results between the second and the first groups, the bigger the pharmacological effectiveness of the studied substance.

Very soon these studies made doctors notice that placebos had much more effects upon the studied diseases than anticipated. In some cases the placebo side-effects outreached those of the active medicine...

Consequently, there was a great increase in scientific researches aiming to clarify what is this effect, why does it happen, what is its physiological bases, etc..

Since the placebo effect can be a real one, calling forth beneficial changes in the patient, it can be very useful in clinical practice. The medical ethics code even allow its use.

Inert placebo - are those really devoid of any action, be it pharmacological, surgical, etc..

Active placebos - are those that actually have actions, although these actions are not specific to the disease for which they are administered.

It is said that placebos have a positive effect when the patients report some improvement in their ailments, and a negative effect when the patients report that they are getting worse or that unpleasant side-effects have occurred (in this last eventuality the placebo is called nocebo, a word derived from the Latin nocere, meaning inflicting damage)

A very interesting conclusion can be drawn: all medicines, besides their actual pharmacological effect, have a placebo effect, and both kinds of effects cannot be easily separated.

Up to now medical science has not fully explained what is the cause (or causes) of the placebo effect. But it seems that it is the result of the patient's expectation of an effect.

Haw can that be explained? There are diverse theories, derived from different psychological schools, that try to explain that fact. We shall adopt here that theory that seems to be the most probable one, that of the conditioned reflex. You sure do remember it: it was discovered when last century was coming to its close by a Russian physiologist by the name of Ivan Pavlov. In 1902 he won the first Nobel Prize on Medicine. He is widely known because of the famous experiment on the dog that salivated whenever it heard a bell (see here a recapitulation about the conduction of these experiments and what we have learned with them).

The general idea is that the placebo effects appears as an involuntary conditioned reflex of the patient's body. We'll next see how this happens.

Conditioned Reflexes

According to Pavlovian theory, the functioning of the nervous system can be understood as depending on reflexes, that are responses to stimuli from the external or internal milieu. A sensorial stimulus, come it from inside or outside the body, reaches a receptor and modifies the organic conditions, and, consequently, calls forth a motor, secretory or vegetative response.

There are two types of reflexes: conditioned and unconditioned.

Unconditioned reflexes are those with which the animals are born, acquired along the evolution of their species, that is, their phylogeny. For example, if we put food in a dog's mouth, saliva begins to flow. This response is preordained inside the dog's nervous system.

Conditioned reflexes are those acquired by the animals during their own lifetime, that is, their ontogeny. These reflexes represent one of the types of learning the nervous system is capable of. As certain stimuli keeps acting on them, the animals form conditioned responses to these stimuli. In order these conditioned responses can appear, they have to be based upon unconditioned ones. In Pavlov's classical experiment, ringing the bell didn't cause the dog to salivate initially. But after he repeatedly rang the bell preceding the unconditioned stimulus (food), the dog began to salivate in response to the ringing of bell alone.

Pavlov defined conditioned reflex as:

"a temporary nervous connection between one of the countless factors of the environment and a very well defined activity of the organism".

In other words, the reflex is a temporary connection linking an environmental stimulus to an unconditioned reflex, thus transformed into a conditioned one, turned on by that until then previously indifferent environmental stimulus.

Modifying reaction to medicines through conditioning

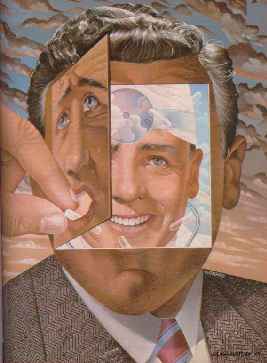

This is a very important topic to help

us understand the placebo effect. We shall try to make it understandable

through a simple experiment:

.

Ilustration: Renato M. E. Sabbatini

|

After a sound stimulus, acetylcholine is injected in a dog. Hypotension (lowering of arterial blood pressure) is the dog's answer to acetylcholine. After several combinations of the sound with the injection, the dog will still show hypotension, even if we inject adrenaline instead of acetylcholine. Since it should normally show hypertension (high blood pressure), this indicates that conditioning completely modified the response to the second agent. The pharmacological action of adrenaline was annulled. An increase in the dog's blood pressure would be the expected reaction to adrenaline injection. Since the animal receives this injection together with a sound stimulus that, for it, is a sign of hypotension, its blood pressure keeps lowering. The dog's body simply ignores the pharmacological action of adrenaline, and obeys the hypotension signal engraved in its central nervous system.

Very important to point up is the fact that several environmental stimuli can unite to each other, forming a chain. Any of those stimuli can act as a sign and turn the conditioned reflex on. Other environmental stimuli, such as entering the room where the experiment takes place, seeing the experimenter or hearing his voice (even out of the room), can thus evoke the same response as the original conditioned stimulus.

Reflexes and language in human beings

And what would happen in a human being? The same thing. There are many experiments showing that man's functions are as conditionable as those of animals. For instance: patients suffering intense pains, caused by a disease called arachnoiditis, were relieved and slept after they received intravenous injections of novocaine (an anesthetic). After some time, the patients still experienced pain relief and slept, although weak saline injections, instead of novocaine, were applied.

In man there is something more important to be considered. According to Pavlov, in animals there exists only what he called the first system of signals of reality. It is made up of these brain systems that receive and analyze stimuli that come both from within and without the organism (for instance, sounds, lights,CO2 levels in the blood, bowel movements, etc.) .

In human beings, there exists, besides the first system of signals, a second one, language, that increases the possibilities of conditioning. For human beings words can function as stimuli, so real and effective, that they can mobilize us just like a concrete stimulus, and even more, sometimes. Because words are symbols, abstractions, the conditioned stimulus can be generalizable.

An example?

If we condition a man applying electric shocks in his hand after he hears the word bell, a defensive reaction ensues and he draws out his hand. After some time, hearing the word bell (in his native tongue or in any other he understands) or seeing a bell (or a picture of one), will cause this man to draw out his hand. Why? Because this man was not conditioned to a group of sounds, as in the dog's case, but to an abstraction, the idea of a bell.

Another example of conditioning in human beings: electric shocks are applied in a subject's hand after he hears the word path, causing his hand to be drawn out. After some time, just hearing the word path is enough to cause the defensive reaction, also induced by synonyms like road, way, route, etc..

Placebo effect as a conditioning

Thus we come to a very convincing physiological explanation about the placebo effect: it is an organic effect that occurs in the patients due to Pavlovian conditioning on the level of abstract and symbolic stimuli.

According to this explanation, what counts is the reality present in the brain, not the pharmacological one. The nervous system expectation in relation to the effects of a drug can annul, revert or enlarge the pharmacological reactions to this drug. This expectation can also cause inert substances to elicit effects that actually don't depend on them.

We could then define placebo effect as the therapeutically positive (or negative) result of expectations implanted in the nervous system of the patients, through conditioning, consequent to the prior use of medicines, contacts with doctors, and information obtained by means of reading and remarks of other people.

The placebo effect can be viewed in

two different ways:

(I) for those doing clinical trials

to study a new medicine in order to evaluate its real value, the placebo

effect is a nuisance: a group of non-medicamentous effects to be eliminated

whenever possible, with the aid of research techniques;

(II) in medical practice, the placebo effect can be useful, because those non-medicamentous effects can be beneficial to the patient. The healing action of specific therapeutic agents, pharmacologically active, can be reinforced by the placebo effect consequent to expectations of cure aroused in the patients in the context of a good doctor-patient relationship. Contrariwise, in the absence of such a good relationship, an important negative placebo effect can ensue, spoiling the compliance to the treatment. The patient simply ignores the prescription or takes the medicines in a completely different way. If he happens to take them in the prescribed way, he will exaggerate all the possible negative effects and will ignore the positive effects of the treatment.

To conclude, we remind that some authors consider that the placebo effect has a dark side, because the cures due to it favor the perpetuation of the use of ineffective and irrational medicinal therapeutic procedures, as those used in the so-called "alternative medicine".

Júlio Rocha do Amaral, MD - Júlio

Rocha do Amaral, MD – Teacher of clinical pharmacology, anatomy and physiology.

Medical Manager of Merck S/A Indústrias Químicas (pharmaceutical

and chemical industries). Redactor of didactic manuals on anatomy, physiology

and pharmacology used by Merck S/A. Editing supervisor of the following

scientific publications: Senecta, Galenus and Sinapse. Redactor of clinical

trials and protocols since 1978. Assistant coordinator of courses on Oxydology

sponsored by the Human Being Institute and UNIGRANRIO (University

of Great Rio). Head of Psychiatric Service. Neurosciences Department. The

Human Being Institute. Co-author of the book "Principles of Neurosciences"

Email: julioamaral@olimpo.com.br

Júlio Rocha do Amaral, MD - Júlio

Rocha do Amaral, MD – Teacher of clinical pharmacology, anatomy and physiology.

Medical Manager of Merck S/A Indústrias Químicas (pharmaceutical

and chemical industries). Redactor of didactic manuals on anatomy, physiology

and pharmacology used by Merck S/A. Editing supervisor of the following

scientific publications: Senecta, Galenus and Sinapse. Redactor of clinical

trials and protocols since 1978. Assistant coordinator of courses on Oxydology

sponsored by the Human Being Institute and UNIGRANRIO (University

of Great Rio). Head of Psychiatric Service. Neurosciences Department. The

Human Being Institute. Co-author of the book "Principles of Neurosciences"

Email: julioamaral@olimpo.com.br |

Renato

M.E. Sabbatini, PhD. holds a doctorate in neurophysiology of behavior

by the School of Medicine of the University of São Paulo at Ribeirão

Preto. He was visiting scholar at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry,

Munich, Germany. Currently, Dr. Sabbatini is associate director of the

Center for Biomedical Informatics and associate professor and Chairman

of Medical Informatics of the Medical School of the State University of

Campinas, Campinas, Brazil. Associate Editor of Brain & Mind. Email:

sabbatin@nib.unicamp.br Renato

M.E. Sabbatini, PhD. holds a doctorate in neurophysiology of behavior

by the School of Medicine of the University of São Paulo at Ribeirão

Preto. He was visiting scholar at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry,

Munich, Germany. Currently, Dr. Sabbatini is associate director of the

Center for Biomedical Informatics and associate professor and Chairman

of Medical Informatics of the Medical School of the State University of

Campinas, Campinas, Brazil. Associate Editor of Brain & Mind. Email:

sabbatin@nib.unicamp.br |